Yes i mean yes i m designer yes i miss you yes i meant yes i m inter yes i m sure yes i miss you chord yes in spanish yes in russian yes in italian yes indeed yes in japanese yes in chinese yes it is

Yes, I'm Autistic. No, I'm Not a STEM Savant

This story is part of Mysteries of the Brain, CNET's deep dive into the human brain's infinite complexities.

Hire them, and you'll have walking supercomputers on your hands: near-infinite processing power and perfect conformity to rules. Sure, they'll short-circuit in social situations and overheat on occasion. But aside from that, they're perfect robots who won't exhibit those bothersome human emotions that can stifle their usefulness.

They are the future of Silicon Valley: Einstein, Gates and Zuckerberg, all rolled into one. As long as you keep them tucked away behind monitors where they can't cause trouble, they'll be your company's greatest assets.

They're the picture of autism.

And they're not real -- no matter how badly companies want them to be.

April marked Autism Acceptance Month here in the US, where more than 1 out of 50 adults have autism, according to an estimate from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

I am one of them. I've spent 22 years navigating a world that views my autism as simultaneously a burden to be stamped out and a commodity to be taken advantage of. Though most of us with autism want to be employed, ignorant attitudes about the disability pervade workplaces, making them less accessible for us.

To be sure, companies have made commendable progress in recent years thanks to advocacy from autistic people and our allies -- and I feel fortunate to work with caring folks who are helping to foster an environment that supports my needs. Some companies have started employee resource groups, consulted autistic people in making their workplaces more accessible and even cultivated hiring programs to train neurodivergent workers.

But these wonderful steps will only go so far when popular misconceptions about autism still permeate workplace culture and guide policy in less-than-accessible directions.

Pigeonholed and misunderstood

The psychologists who knew me as a toddler would consider it a miracle I'm even employed in the first place. I was diagnosed at age 3 with Asperger's Syndrome, a neurological and developmental condition that's nowadays classified as simply autism spectrum disorder. (That change in terminology is a good thing: Austrian autism researcher Hans Asperger was shown to have collaborated with the Nazi regime.)

Researchers aren't sure what causes autism. I struggled to interact with my preschool peers, "melted down" when switching from one activity to another, and sobbed in grocery stores because the fluorescent lights felt like daggers in my eyes. "What time is it?" my dad would ask me. "Wednesday," I'd respond. It's not that I didn't know the answer, it's that I didn't understand the question due to my auditory processing difficulties.

Doctors told my parents I'd never be able to drive or live independently. "Mary often appears to be staring through you rather than looking at you," reads one preschool teacher's remark in my file. "During free-choice time, she just sits in the middle of the floor and stares."

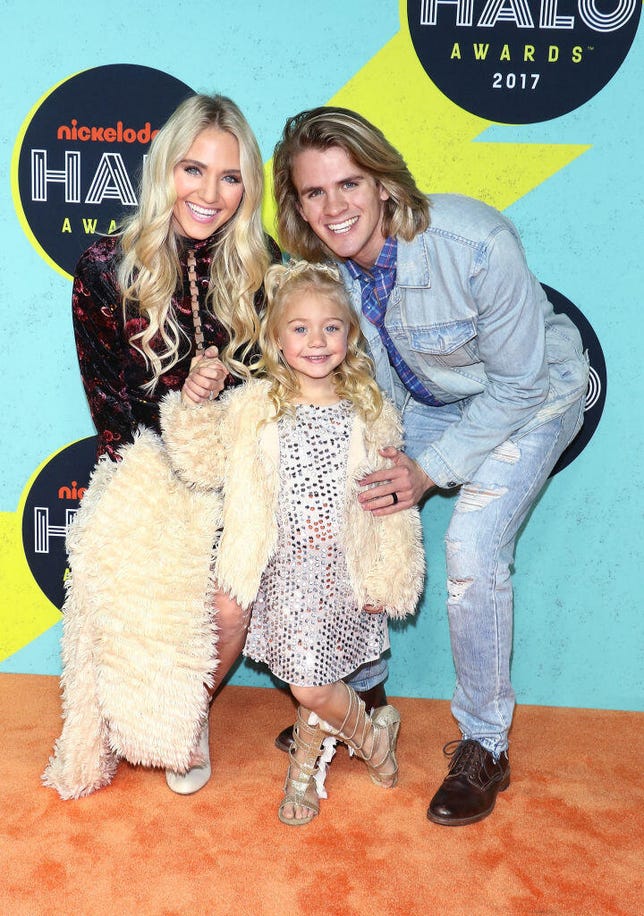

CNET Associate Editor Mary King, a 22-year-old autistic woman, works at her desk in the Charlotte, North Carolina, headquarters of Red Ventures, CNET's parent company. On some days, parts of the office are still relatively empty due to the pandemic.

Anna Throckmorton/Red VenturesI'm exceptionally lucky my loving parents had the resources to send me to occupational and speech therapy, which were critical in teaching me how to speak, interact with others and handle my sensory challenges. Like many autistic people, especially those socialized as women, I observed my neurotypical peers and learned to "mask": putting on a manufactured personality to hide my autistic traits, even as it exhausted me to the point of tears by the end of the day.

By the time I was about 10, I reached a point where the untrained eye couldn't clock me as autistic. I excelled at school and standardized tests, especially in the humanities. Then I'd go home and shut down, drained from the masking and sensory overload. When my parents would show my teachers my diagnosis and ask for a simple accommodation -- like the option for me to go sit in the school library for a few minutes to calm my overstimulated brain -- they would respond with dismay, disbelief and outright dismissal because I didn't match their preconceived notions about autism.

Read more stories in CNET's ongoing series Mysteries of the Brain.

As a result, I'm all too familiar with the popular idea of what autism looks like. We're all male. White. We're either deemed high-functioning, perfect performers with savant-level STEM abilities that companies can harness for profit, or we're pigeonholed as low-functioning and written off altogether because we aren't "useful." In addition to arguing that autism "functioning labels" do more harm than good, journalist Eric Garcia, who is himself on the spectrum, identifies these as the two myths that plague autistic people in the workforce.

"These narratives put the onus on autistic people to find a super skill that will make them an asset to employers rather than forcing employers to become more accepting of autistic workers," Garcia writes in his 2021 book We're Not Broken: Changing the Autism Conversation.

Autistic workers need acceptance and support from our employers, Garcia and others stress, regardless of how our autism manifests. Autism spectrum disorder involves difficulties with sensory processing, communication and executive functioning, with the key word here being "spectrum." (Here's a great comic explaining how the autism spectrum is better described as a spider graph than a straight line.)

It looks different from person to person, and studies haven't found a consistent autistic brain composition. Our challenges and abilities vary greatly. Most autistic people, myself included, are not savants. But sometimes autism lends us special skills in areas like memory, pattern recognition and visual thinking.

"People with autism might see the world through a filter that enhances the intensity of the details of the images they see every moment of their lives," researcher Arjen Alink told the autism-focused news outlet Spectrum News in 2021.

Autism exists in every ethnicity and gender, though research shows autistic people of color and women have a harder time accessing diagnoses and support. And contrary to the stereotypes, we're employed in every field. Sure, we're scientists, engineers, software developers and tradespeople, but we're also artists, retail workers, communications professionals and businesspeople.

We share your desks and break rooms. When we choose to disclose our autism to you and communicate the work conditions that would help us succeed, please believe us, even if we look, talk or act differently than what you're expecting. Even if we don't remind you of Sheldon Cooper from The Big Bang Theory, or Dustin Hoffman's character in Rain Man, or your aunt's neighbor's cousin's autistic fifth grader who's enrolled in linear algebra.

Not a human calculator

"They think we're like calculators," Gideon Kariuki, a 21-year-old public policy student at Arizona State University, told me.

"We're members of the community, too," says Gideon Kariuki, a junior at Arizona State University. "Regardless of our support needs, regardless of, quote unquote, 'what we can contribute to society.'"

Margarete MoffettKariuki is, in fact, anything but a human calculator: He said he's always been "awful" at math. Instead, his passion lies in civics, public service and policy. He reckons his sharp analytical thinking -- an ability commonly found among autistic folks -- has served him well in these areas.

The night we spoke, he was headed to a concert featuring one of his friends from Blaze Radio, the student radio station at Arizona State. Kariuki is Blaze Radio's program director, and he co-hosts two news analysis shows there.

"I'm somebody who's a big old chatterbox, as I'm sure you're figuring out," Kariuki said with a laugh.

Being an autistic chatterbox myself, I had a splendid time talking with Kariuki as we derailed the interview and led each other down rabbit trails only tangentially related to the topic at hand. At one point we landed on the subject of US immigration policy and his parents' emigration from Kenya. That's when he made a compelling connection between attitudes toward immigrants and autistic people.

"One of the things that drives me up a wall concerning American immigration rhetoric is, 'Immigrants are such a benefit to the economy, yada yada.' Listen, I agree with that," he said. "However, that's not why you should support immigration."

The US should support immigrants not solely for the potential economic benefits, Kariuki argues, but because it's the right thing to do. By similar logic, while autistic workers can benefit employers with the special abilities and helpful traits we often bring to the table, that's not the primary reason workplaces should treat us with respect.

"We're members of the community, too," he said. "Regardless of our support needs, regardless of, quote unquote, 'what we can contribute to society.'"

What support looks like

For 32-year-old New York City-based video producer Hunter Boone, who uses both "he" and "they" pronouns, support in the workplace could look as simple as supervisors being more direct with their communication. Boone said they've noticed that once they reveal they're on the spectrum, supervisors tend to start speaking to them as if they were a toddler. With a newfound hyper-awareness of Boone's condition and a desire to avoid offending or confusing him, the supervisors start to be even less direct: the opposite of what Boone needs.

"I crave communication," Boone told me.

For instance, one time his boss assigned them a task, and Boone completed it correctly. But afterward, Boone's boss told him he actually didn't intend for Boone to take the assignment literally. It had been difficult for Boone to discern that, as the interaction had taken place over the messaging platform Slack, where he couldn't see his boss' facial expressions or tone of voice to understand his meaning. It's a classic hangup that can happen as neurotypical and neurodivergent people work together, Boone said. More direct communication can help make things smoother.

Tim Johnson, an autistic 24-year-old notary public in Virginia and a friend from college, said the best thing that could happen for him in a workplace would be for people to stop expecting him to socialize exactly like they do.

"If I could hand out a business-card-sized little written thing saying, 'Hey, I'm probably not going to look you in the eye. Probably going to listen a lot more than I speak. I'm probably going to take criticism badly,' and not be socially judged for it, I would do it in a heartbeat," Johnson told me.

That's a brilliant idea. If I had a little "Hey! I'm autistic!" handout like Johnson described, mine would ask managers to be very direct and literal when they assign me tasks; that might have helped Boone, too. Mine would also say I might accidentally come across as snarky or overly blunt, but I'm being earnest 99% of the time -- just ask me for clarification. Finally, I would say I struggle with multitasking and bouncing between tasks at a moment's notice. When we advocate for ourselves by expressing our needs, it's important for employers to welcome that self-advocacy and join us in developing solutions.

Johnson's job requires him to take on requests for support as they come in, and he's had to manage his own expectation that he has to respond to every incoming message immediately. (I have trouble with that, too -- thanks a lot, Slack.) His standing desk has been helping him "take a literal step back": To fidget, he shakes out his arms, and that helps bring his stress back down to a manageable level. We discussed how dogs (beagles being one of Johnson's special interests, a term used in the autism field to describe areas of intense focus) do a similar sort of shaking motion to reset.

"Whenever my dog does it, it's when she comes in from the rain and she's getting all the rainwater off," Johnson said. "It's essentially the same thing, but with stress, for me."

Taking a fidget break

Sometimes the very nature of work can be difficult for autistic people to navigate, so we innovate ways to tend to our own needs. For example, I struggle when I'm interrupted in the middle of a task and told to go do something else. Sure, I can technically do it, but my brain will feel fried, making it more difficult to complete the rest of the day's work.

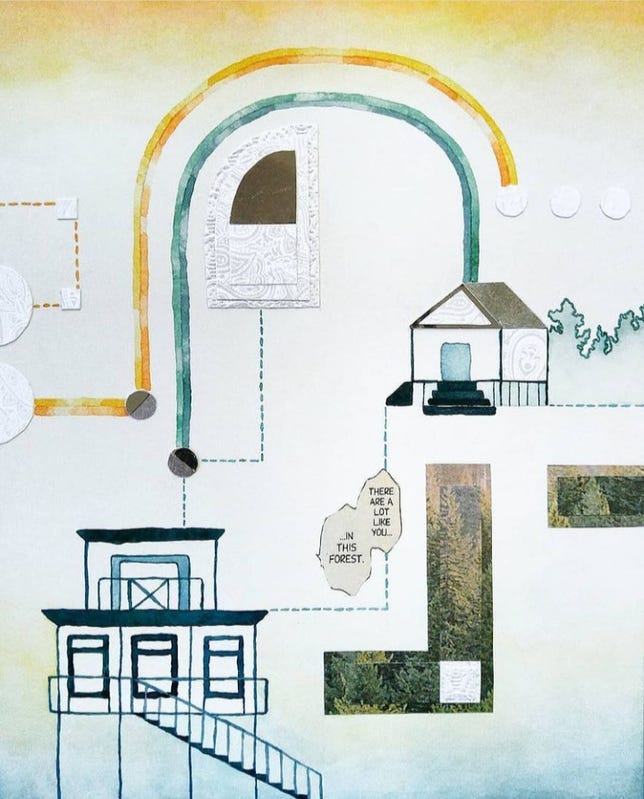

Cara Larsen's mixed media art (on Instagram at @caralarsenart). "The arts can be a haven for autistic people, an environment where our traits and talents can be appreciated, and we can express ideas we may not be able to say in words," Larsen wrote in a blog post for Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network.

Cara LarsenKarisa, my understanding and supportive manager at CNET, lets me block out time on my calendar each day to focus on long-term projects, uninterrupted by day-to-day tasks. (This is a good idea for everyone, autistic or not.) I still get all of those tasks done: I just do it in a way that works for both me and my team. Managers can help by letting us do what we need to do. Allow us to take a step back and fidget, like Johnson. Or let us complete tasks in a workflow that works for us, even if it seems strange to you.

Cara Larsen, a 29-year-old autistic artist, prefers to complete her art in "bursts": She'll work for a few minutes, then pace around or read for a while before going back to her creation. Or she'll hop on her swing -- mounted indoors, to escape the overwhelming Mississippi humidity -- to gaze at one of her works in progress and contemplate her next course of action.

I conducted my interview with Larsen via email, as she said typing can often be easier for her than speaking. While growing up, she told me, teachers would try to shoehorn her into what she calls "the autistic STEM genius stereotype" despite her struggling with math. When she was deciding on a major in community college, she told instructors and advisers she was good at art and design, but they would immediately shoot her down.

"No one really encouraged me to explore different types of design careers, but I was constantly pushed toward STEM because in their eyes, that's what smart people did," Larsen told me.

She said she's suffered a lot of impostor syndrome as a result of these experiences. Larsen also discussed this in a 2018 blog post for Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network, in which she argues that even seemingly positive stereotypes are still harmful for autistic people.

"The 'autistic math genius' stereotype may seem better than 'gifted kids who struggle in school are just lazy' or 'girls can't do math' or 'art majors don't get jobs,' but it can limit a person's future just as much as those more negative stereotypes can -- especially when it is combined with them," Larsen wrote.

April is Autism Acceptance Month. While I appreciate the blue balloons for autism awareness, I'd encourage companies to also direct energy toward creating more accessible work environments.

Kaipong/Getty ImagesI asked Larsen if there's any sort of community of autistic artists. I was curious, as that's not a profession stereotypically associated with autism. She said she's met a few, but wishes there was more support in place for artists on the spectrum. They may have trouble affording supplies, as many autistic people are low-income, studies show.

"No-strings-attached grants for low-income autistic artists, with an easy application process," she suggests. "And help promoting yourself at art-related events."

From artists' circles to media organizations, you probably work with an autistic person regardless of your field. Instead of wearing a blue shirt for autism awareness, celebrate Autism Acceptance Month by making a conscious effort to listen to our needs and support us.

The many faces of focus

Often, it's in the little things. For example: Zoom calls. People often perceive my neutral facial expression as glazed over, checked out or irritated, even when I'm feeling perfectly fine and focusing intently. So when my camera is on, I have to devote energy to putting on my "pleasant, active listening face" and looking like I'm paying attention. (Ironically, this makes it more difficult for me to actually pay attention!) Because of this, I tend to focus much better when my camera is turned off. To some people, though, this indicates the opposite: that I'm not listening.

Instead of enforcing a strict camera-on policy and assuming we're less dedicated employees when we turn our cameras off, understand that focusing can take many shapes.

Like Hunter Boone said, sometimes we need you to be more direct. Like Tim Johnson said, sometimes we don't conform to social expectations. Like Cara Larsen said, sometimes we just work a little differently than you.

Read more: What You Need to Know About Autism Spectrum Disorder

Source