TikTok Parents Are Taking Advantage of Their Kids. It Needs to Stop

Rachel Barkman's son started accurately identifying different species of mushroom at the age of 2. Together they'd go out into the mossy woods near her home in Vancouver and forage. When it came to occasionally sharing in her TikTok videos her son's enthusiasm and skill for picking mushrooms, she didn't think twice about it -- they captured a few cute moments, and many of her 350,000-plus followers seemed to like it.

That was until last winter, when a female stranger approached them in the forest, bent down and addressed her son, then 3, by name and asked if he could show her some mushrooms.

"I immediately went cold at the realization that I had equipped complete strangers with knowledge of my son that puts him at risk," Barkman said in an interview this past June.

This incident, combined with research into the dangers of sharing too much, made her reevaluate her son's presence online. Starting at the beginning of this year, she vowed not to feature his face in future content.

"My decision was fueled by a desire to protect my son, but also to protect and respect his identity and privacy, because he has a right to choose the way he is shown to the world," she said.

These kinds of dangers have cropped up alongside the rise in child influencers, such as 10-year-old Ryan Kaji of Ryan's World, who has almost 33 million subscribers, with various estimates putting his net worth in the multiple tens of millions of dollars. Increasingly, brands are looking to use smaller, more niche, micro- and nano-influencers, developing popular accounts on Instagram, TikTok and YouTube to reach their audiences. And amid this influencer gold rush there's a strong incentive for parents, many of whom are sharing photos and videos of their kids online anyway, to get in on the action.

The increase in the number of parents who manage accounts for their kids -- child influencers' parents are often referred to as "sharents" -- opens the door to exploitation or other dangers. With almost no industry guardrails in place, these parents find themselves in an unregulated wild west. They're the only arbiters of how much exposure their children get, how much work their kids do, and what happens to money earned through any content they feature in.

Instagram didn't respond to multiple requests for comment about whether it takes any steps to safeguard child influencers. A representative for TikTok said the company has a zero-tolerance approach to sexual exploitation and pointed to policies to protect accounts of users under the age of 16. But these policies don't apply to parents posting with or on behalf of their children. YouTube didn't immediately respond to a request for comment.

"When parents share about their children online, they act as both the gatekeeper -- the one tasked with protecting a child's personal information -- and as the gate opener," said Stacey Steinberg, a professor of law at the University of Florida and author of the book Growing Up Shared. As the gate opener, "they benefit, gaining both social and possibly financial capital by their online disclosures."

The reality is that some parents neglect the gatekeeping and leave the gate wide open for any internet stranger to walk through unchecked. And walk through they do.

Meet the sharents

Mollie is an aspiring dancer and model with an Instagram following of 122,000 people. Her age is ambiguous but she could be anywhere from 11-13, meaning it's unlikely she's old enough to meet the social media platform's minimum age requirement. Her account is managed by her father, Chris, whose own account is linked in her bio, bringing things in line with Instagram's policy. (Chris didn't respond to a request for comment.)

You don't have to travel far on Instagram to discover accounts such as Mollie's, where grown men openly leer at preteen girls. Public-facing, parent-run accounts dedicated to dancers and gymnasts -- who are under the age of 13 and too young to have accounts of their own -- number in the thousands. (To protect privacy, we've chosen not to identify Mollie, which isn't her real name, or any other minors who haven't already appeared in the media.)

Parents use these accounts, which can have tens of thousands or hundreds of thousands of followers, to raise their daughters' profiles by posting photos of them posing and demonstrating their flexibility in bikinis and leotards. The comment sections are often flooded with sexualized remarks. A single, ugly word appeared under one group shot of several young girls in bikinis: "orgy."

Some parents try to contain the damage by limiting comments on posts that attract too much attention. The parent running one dancer account took a break from regular scheduling to post a pastel-hued graphic reminding other parents to review their followers regularly. "After seeing multiple stories and posts from dance photographers we admire about cleaning up followers, I decided to spend time cleaning," read the caption. "I was shocked at how many creeps got through as followers."

But "cleaning up" means engaging in a never-ending game of whack-a-mole to keep unwanted followers at bay, and it ignores the fact that you don't need to be following a public account to view the posts. Photos of children are regularly reposted on fan or aggregator accounts, over which parents have no control, and they can also be served up through hashtags or through Instagram's discovery algorithms.

The simple truth is that publicly posted content is anyone's for the taking. "Once public engagement happens, it is very hard, if not impossible, to really put meaningful boundaries around it," said Leah Plunkett, author of the book Sharenthood and a member of the faculty at Harvard Law School.

This concern is at the heart of the current drama concerning the TikTok account @wren.eleanor. Wren is an adorable blonde 3-year-old girl, and the account, which has 17.3 million followers, is managed by her mother, Jacquelyn, who posts videos almost exclusively of her child.

Concerned onlookers have pointed Jacquelyn toward comments that appear to be predatory, and have warned her that videos in which Wren is in a bathing suit, pretending to insert a tampon, or eating various foodstuffs have more watches, likes and saves than other content. They claim her reluctance to stop posting in spite of their warnings demonstrates she's prioritizing the income from her account over Wren's safety. Jacquelyn didn't respond to several requests for comment.

Last year, the FBI ran a campaign in which it estimated that there were 500,000 predators online every day -- and that's just in the US. Right now, across social platforms, we're seeing the growth of digital marketplaces that hinge on child exploitation, said Plunkett. She doesn't want to tell other parents what to do, she added, but she wants them to be aware that there's "a very real, very pressing threat that even innocent content that they put up about their children is very likely to be repurposed and find its way into those marketplaces."

Naivete vs. exploitation

When parent influencers started out in the world of blogging over a decade ago, the industry wasn't exploitative in the same way it is today, said Crystal Abidin, an academic from Curtin University who specializes in internet cultures. When you trace the child influencer industry back to its roots, what you find is parents, usually mothers, reaching out to one another to connect. "It first came from a place of care among these parent influencers," she said.

Over time, the industry shifted, centering on children more and more as advertising dollars flowed in and new marketplaces formed.

Education about the risks hasn't caught up, which is why people like Sarah Adams, a Vancouver mom who runs the TikTok account @mom.uncharted, have taken it upon themselves to raise the flag on those risks. "My ultimate goal is just have parents pause and reflect on the state of sharenting right now," she said.

But as Mom Uncharted, Adams is also part of a wider unofficial and informal watchdog group of internet moms and child safety experts shedding light on the often disturbing way in which some parents are, sometimes knowingly, exploiting their children online.

The troubling behavior uncovered by Adams and others suggests there's more than naivete at play -- specifically when parents sign up for and advertise services that let people buy "exclusive" or "VIP" access to content featuring their children.

Some parent-run social media accounts that Adams has found linked out to a site called SelectSets, which lets the parents sell photo sets of their children. One account offered sets with titles such as "2 little princesses." SelectSets has described the service as "a classy and professional" option for influencers to monetize content, allowing them to "avoid the stigma often associated with other platforms."

Over the last few weeks, SelectSets has gone offline and no owner could be traced for comment.

In addition to selling photos, many parent-run dancer accounts, Mollie's included, allow strangers to send the dancers swimwear and underwear from the dancers' Amazon wish lists, or money to "sponsor" them to "realize their dream" or support them on their "journeys."

While there's nothing technically illegal about anything these parents are doing, they're placing their children in a gray area that's not explicitly sexual but that many people would consider to be sexualized. The business model of using an Amazon wish list is one commonly embraced by online sugar babies who accept money and gifts from older men.

"Our Conditions of Use and Sale make clear that users of Amazon Services must be 18 or older or accompanied by a parent or guardian," said an Amazon spokesperson in a statement. "In rare cases where we are made aware that an account has been opened by a minor without permission, we close the account."

Adams says it's unlikely to be other 11-year-olds sending their pocket money to these girls so they attend their next bikini modeling shoot. "Who the fuck do you think is tipping these kids?" she said. "It's predators who are liking the way you exploit your child and giving them all the content they need."

Turning points

Plunkett distinguishes between parents who are casually sharing content that features their kids and parents who are sharing for profit, an activity she describes as "commercial sharenting."

"You are taking your child, or in some cases, your broader family's private or intimate moments, and sharing them digitally, in the hope of having some kind of current or future financial benefit," she said.

No matter the parent's hopes or intentions, any time children appear in public-facing social media content, that content has the potential to go viral, and when it does, parents have a choice to either lean in and monetize it or try to rein it in.

During Abidin's research -- in which she follows the changing activities of the same influencers over time -- she's found that many influencer parents reach a turning point. It can be triggered by something as simple as other children at school being aware of their child's celebrity or their child not enjoying it anymore, or as serious as being involved in a car chase while trying to escape fans (an occurrence recounted to Abidin by one of her research subjects).

One influencer, Katy Rose Pritchard, who has almost 92,000 Instagram followers, decided to stop showing her children's faces on social media this year after she discovered they were being used to create role-playing accounts. People had taken photos of her children that she'd posted and used them to create fictional profiles of children for personal gratification, which she said in a post made her feel "violated."

All these examples highlight the different kinds of threats sharents are exposing their children to. Plunkett describes three "buckets" of risk tied to publicly sharing content online. The first and perhaps most obvious are risks involving criminal and/or dangerous behavior, posing a direct threat to the child.

The second are indirect risks, where content posted featuring children can be taken, reused, analyzed or repurposed by people with nefarious motives. Consequences include anything from bullying to harming future job prospects to millions of people having access to children's medical information -- a common trope on YouTube is a video with a melodramatic title and thumbnail involving a child's trip to the hospital, in which influencer parents with sick kids will document their health journeys in blow-by-blow detail.

The third set of risks are probably the least talked about, but they involve potential harm to a child's sense of self. If you're a child influencer, how you see yourself as a person and your ability to develop into an adult is "going to be shaped and in some instances impeded by the fact that your parents are creating this public performance persona for you," said Plunkett.

Often children won't be aware of what this public persona looks like to the audience and how it's being interpreted. They may not even be aware it exists. But at some point, as happened with Barkman, the private world in which content is created and the public world in which it's consumed will inevitably collide. At that point, the child will be thrust into the position of confronting the persona that's been created for them.

"As kids get older, they naturally want to define themselves on their own terms, and if parents have overshared about them in public spaces, that can be difficult, as many will already have notions about who that child is or what that child may like," said Steinberg. "These notions, of course, may be incorrect. And some children may value privacy and wish their life stories were theirs -- not their parents -- to tell."

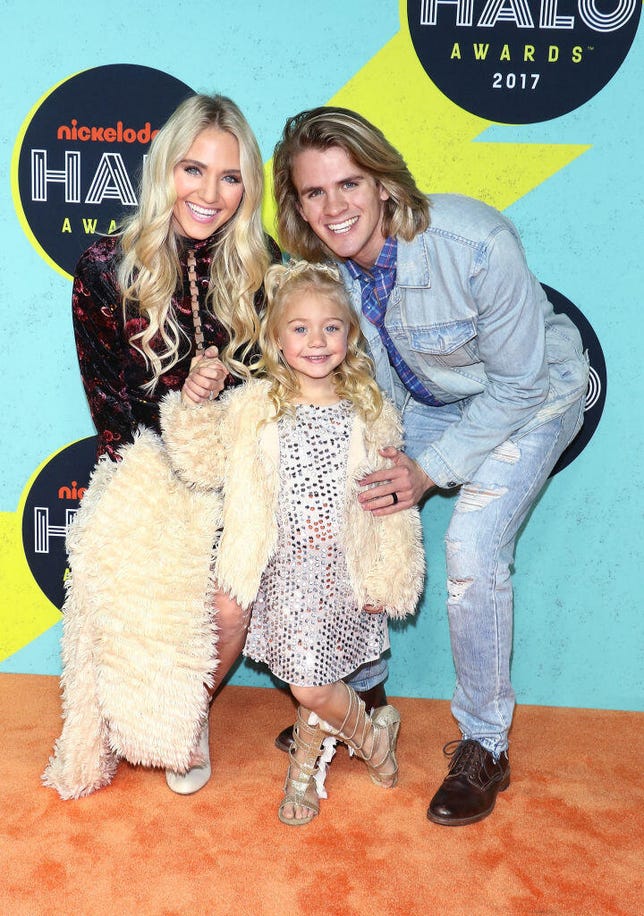

Savannah and Cole LaBrant have documented nearly everything about their children's lives.

Jim Spellman/WireImageThis aspect of having their real-life stories made public is a key factor distinguishing children working in social media from children working in the professional entertainment industry, who usually play fictional roles. Many children who will become teens and adults in the next couple of decades will have to reckon with the fact that their parents put their most vulnerable moments on the internet for the world to see -- their meltdowns, their humiliation, their most personal moments.

One influencer family, the LaBrants, were forced to issue a public apology in 2019 after they played an April Fools' Day Joke on their 6-year-old daughter Everleigh. The family pretended they were giving her dog away, eliciting tears throughout the video. As a result, many viewers felt that her parents, Sav and Cole, had inflicted unnecessary distress on her.

In the past few months, parents who film their children during meltdowns to demonstrate how to calm them down have found themselves the subject of ire on parenting Subreddits. Their critics argue that it's unfair to post content of children when they're at their most vulnerable, as it shows a lack of respect for a child's right to privacy.

Privacy-centric parenting

Even the staunchest advocates of child privacy know and understand the parental instinct of wanting to share their children's cuteness and talent with the world. "Our kids are the things usually we're the most proud of, the most excited about," said Adams. "It is normal to want to show them off and be proud of them."

When Adams started her account two years ago, she said her views were seen as more polarizing. But increasingly people seem to relate and share her concerns. Most of these are "average parents," naive to the risks they're exposing their kids to, but some are "commercial sharents" too.

Even though they don't always see eye to eye, the private conversations she's had with parents of children (she doesn't publicly call out anyone) with massive social media presences have been civil and productive. "I hope it opens more parents' eyes to the reality of the situation, because frankly this is all just a large social experiment," she said. "And it's being done on our kids. And that just doesn't seem like a good idea."

For Barkman, it's been "surprisingly easy, and hugely beneficial" to stop sharing content about her son. She's more present, and focuses only on capturing memories she wants to keep for herself.

"When motherhood is all consuming, it sometimes feels like that's all you have to offer, so I completely understand how we have slid into oversharing our children," she said. "It's a huge chunk of our identity and our hearts."

But Barkman recognizes the reality of the situation, which is that she doesn't know who's viewing her content and that she can't rely on tech platforms to protect her son. "We are raising a generation of children who have their entire lives broadcast online, and the newness of social media means we don't have much data on the impacts of that reality on children," she said. "I feel better acting with caution and letting my son have his privacy so that he can decide how he wants to be perceived by the world when he's ready and able."

Source

Tags:

- About Tiktok For Parents

- Tiktok Guide For Parents

- Parent Reviews Of Tiktok

- What Parents Should Know About Tiktok

- Parent Reviews Of Tiktok

- Tiktok Guide For Parents

- What Parents Need To Know About Tiktok

- What Is Tiktok For Parents

- Does Tiktok Have Parental Settings

- About Tiktok For Parents

- Why Are Parents Suspicious Of Tiktok

- Tiktok Parental Restrictions